On July 9, 2016, a 19-year-old female student at the University of Cincinnati was visiting a friend at University Park Apartments. According to a UC Police Department report, the student became sick and was led to the bathroom by 19-year-old Geonte West, who then anally raped her. That same day, a friend of the student reported the assault to UC police.

However, UC officials failed to issue a timely alert to notify students, staff, parents and other UPA residents of the reported rape. By federal law under the Clery Act, universities are required to issue a timely warning regarding any ongoing threat to campus.

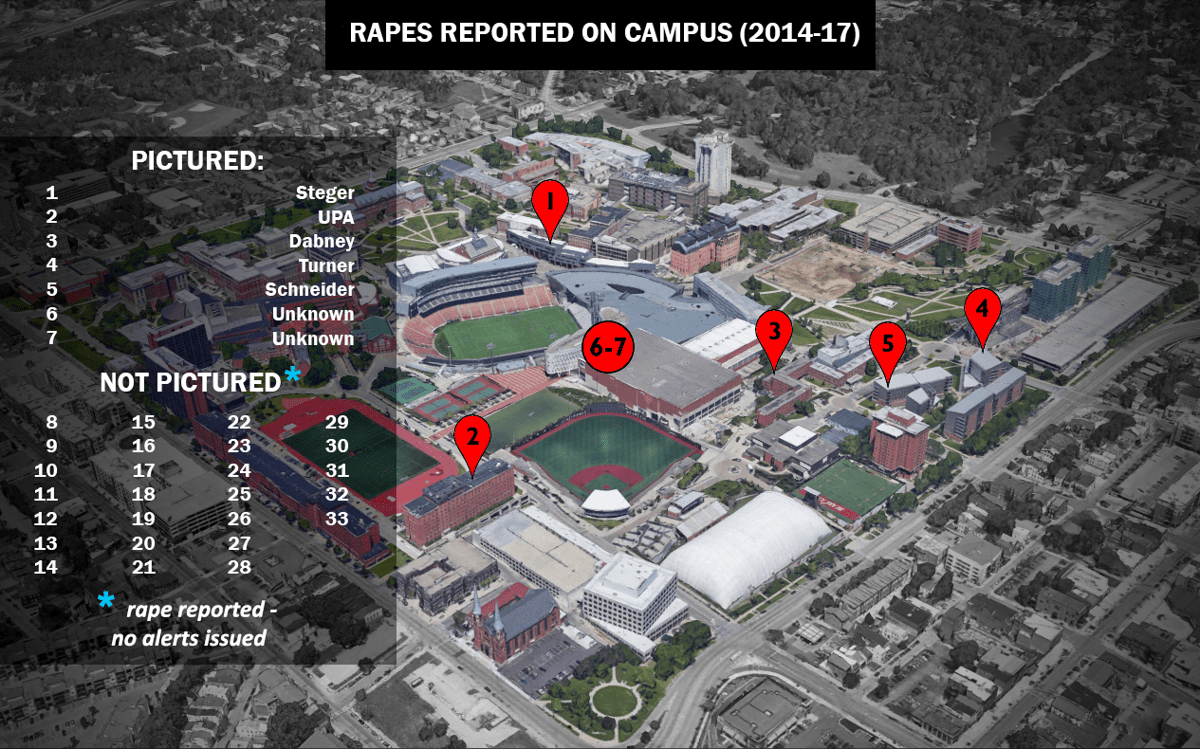

Failure to issue crime alerts for sexual assaults reported on campus is not uncommon for UC. Between 2014 and 2017, 33 on-campus rapes were reported to UC officials, federal records show. Of those, UC officials issued crime alerts for just seven.

In other words, officials failed to issue crime alerts for nearly 80 percent of rapes reported on campus.

James Whalen, UC’s director of public safety since 2015, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Kelly Cantwell, the associate public information officer who answered on Whalen’s behalf, encouraged The News Record to seek another source who is more informed on matters related to crime alerts.

Nicole Smith, Clery compliance coordinator, said the university is not always obligated to issue timely crime alerts.

“[If] there is an ongoing threat, we’re obligated to send out a timely warning,” Smith said. “We may not send out a timely warning if there’s not an eminent threat.”

Related: Opinion | How to be an active bystander to prevent sexual assault on campus

Smith cited a hypothetical example where a sexual assault suspect is arrested and booked, which would likely negate any immediate threat to campus. In cases like these, the university “would not send out a timely warning,” Smith said, “because we don’t need to notify the students that there is a suspect on the loose, because he or she has been captured.”

The Clery Act is named after Jeanne Clery, a first-year student who was raped and murdered in her dormitory at Lehigh University in 1986. In the three years preceding her enrollment, 38 violent crimes were committed on campus, but officials did not notify students about them.

Her parents, Howard and Connie Clery, later said they would not have allowed their daughter to attend Lehigh had they known about its violent crime rate. They launched a campaign to convince the government to require colleges to disclose campus crime statistics, and in 1990, Congress approved the Clery Act, which requires universities to publish annual crime reports, maintain detailed daily crime logs and issue timely warnings about any ongoing threats on campus.

UC officials have insisted the university strives for transparency in reporting sexual assaults. Yet the university’s response to reported rapes in residence halls tells a different story.

Related: Opinion | UC needs to take sexual assault more seriously

Twenty-three rapes were reported in UC residence halls between 2014 and 2017, yet officials issued just five crime alerts notifying students about them, according to federal and UC records. In 2016, seven rapes were reported in residence halls, yet UC officials issued crime alerts for just two of them.

Only one alert identified the building where the rape reportedly occurred, records show.

Smith said officials include the location of each reported rape — including the names of residence halls — in crime alerts.

“As for the location, we will put a block or a building number, or building name, on campus,” she said. “We will use a building name, Morgens Hall, Turner Hall, or we’ll say the 2300 block of Ohio Avenue.”

However, UC officials did not disclose a location in an Oct. 13, 2016, crime alert, which said that a sexual assault had been reported that day “in a residence hall.”

In an Oct. 24, 2016, crime alert, UC officials identified University Park Apartments (UPA) as the residence hall where a sexual assault reportedly took place. However, three other rapes at UPA were reported to UC police in 2016, according to UC’s 2016 Campus Crime Report, and crime alerts were not issued for any of them.

Bethany White was a resident adviser in 2016 at UPA. She told The News Record she only learned about sexual assaults at UPA if they were reported to resident advisers.

White said UC officials have not fully recognized the magnitude of sexual assaults in campus housing.

“I believe the knowledge is there,” she said. “But resources, response training and general university culture has not caught up to the reality of sexual assaults or harassment.”

Related: Opinion | The hidden costs of being a sexual assault survivor

The first reported sexual assault in 2016 at UPA occurred April 8. According to a UC police report, a female UC student said a male student forced her to perform oral sex.

UC officials did not issue a crime alert.

Three months later, a second rape was reported at UPA: the one where a UC student said Geonte West anally raped her July 9, according to a UC police report.

Once again, UC officials did not issue a crime alert.

On July 28 — almost three weeks later — officials issued a UC Aware email that said a student had reported being sexually assaulted July 9 in a residence hall. The email did not identify which residence hall the assault was reported in.

On Aug. 25, a Hamilton County grand jury indicted West on charges of rape and sexual battery, according to court records, which identify the survivor as “C.W.” According to the indictment, West “knew C.W. was intoxicated when he led her into the bathroom, closed the door and sexually assaulted C.W.”

West entered a plea of not guilty to each count.

Eighteen months later, West and Hamilton County Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Christopher Lipps agreed to a plea bargain. On March 19, 2018, West pleaded guilty to felonious assault, and the prosecutor dropped all other charges, court records show.

Lipps was unable to be reached. West refused to comment.

In May 2018, Hamilton County Common Pleas Judge Melba Marsh sentenced West to five years’ probation, court records show.

Avanti Patel moved into UPA in August 2016 — one month after C.W. reported that West had raped her in the same complex. Patel said UC officials never notified her about the reported rape. Had they done so, she said, “that would definitely have played into my decision of living there.”

Patel, who still lives in UPA, said better alerting students about reported rapes would raise awareness about many safety issues. For example, Patel said UPA residents often stand near the entrance and open the door to anyone who approaches.

Patel said she hopes UC officials would be more transparent when it comes to alerting students about reports of sexual assault.

“It’s concerning that they’re not saying anything about it or [issuing] any follow-up about it,” she said.

Sexual assault on college campuses is a national problem. In a web-based survey commissioned by the U.S. Department of Justice in 2007, roughly 19 percent of female respondents reported experiencing “completed or attempted sexual assault” since entering college.

The university’s response to reports of sexual assault at UC has been a flashpoint of controversy for years. In 2016, a student-led movement known as Students for Survivors demanded officials address what the group called UC’s “sexually hostile environment.”